Privacy Rights in the Thai Context

Privacy Rights in the Thai Context

By COFACT Thailand

In light of COVID-19 crisis, it’s not only the virus that has widely spread but disclosure of personal information also causes harm to privacy rights of Thai people and the families tend to “get ripped apart online” because of pandemic overreaction.

During the 14th Year-end Digital Thinkers Forum organized by COFACT and networks of civil society organizations on 26 November 2020, Ms.Thitirat Thipsamritkul, a lecturer at Thammasat University’s Faculty of Law presented a paper titled “Thailand’s lessons learned to earn public’s trust in data security in addressing the pandemic” that highlights conflict between individual rights and public health. The details are shown below.

Ms. Thitirat said contact-tracing application is necessary and conducted by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a way to control and prevent COVID-19 and other communicable diseases. However, the government’s request for “necessary” personal information to track COVID-19 cases remains questionable because if the state requests “unrelated” personal information, this means that personal data of Thai people may be threatened. Thus, conflict between privacy and public health grows. Not only that, families of patients with COVID-19 are also being affected in most cases.

“Over the past year, laws governing the personal data protection remains unclear with the enforcement of the Personal Data Protection Act (2019) being postponed by a year due to the COVID-19. The government should be more concerned about economy, not data protection during the coronavirus pandemic. But the ministry issued an announcement, ensuring data security and its rights to access people’s personal information. At present, only the public sector is subject to private data protection as stipulated in the Official Information Act (1997) that shares the same logic with the Personal Data Protection Act (2019). People’s personal data, thus, can be used for the purpose of public health,” Ms. Thitirat explained.

The first case is Fit-to-Fly health certificate that confirms passengers are fit to fly. The certificate, however, doesn’t guarantee if they pose risk of being infected. The certificate undoubtedly sparked public concerns over the necessity of the state’s request for personal data in bringing the virus under control.

To summarize, three principles should be taken into consideration when it comes to protecting personal data – the use of data to combat pandemics, transparency (such as who acknowledges disclosure of data, how long data is stored, and is data used fairly) and data security (protecting the confidentiality of data). Thus, there’re lessons from past pandemics for everyone to learn.

Personal information is a double-edged sword

Disclosing personal information to other people can put everyone at “greater risk”. Ms. Thitirat has listed five case studies and shared them with the audience. He questioned all events that led to thought-provoking discussions.

The second case involves a quarantine app that has been rolled out to track and monitor people arriving from foreign countries that are heavily hit by the coronavirus. The application requests information such as body temperature. Concerns raised over the necessity of such questions.

The third case is the leaking of the passengers’ personal information, including full names, passport numbers, addresses and flight numbers. Some of personal details that should not be made publicly became available.

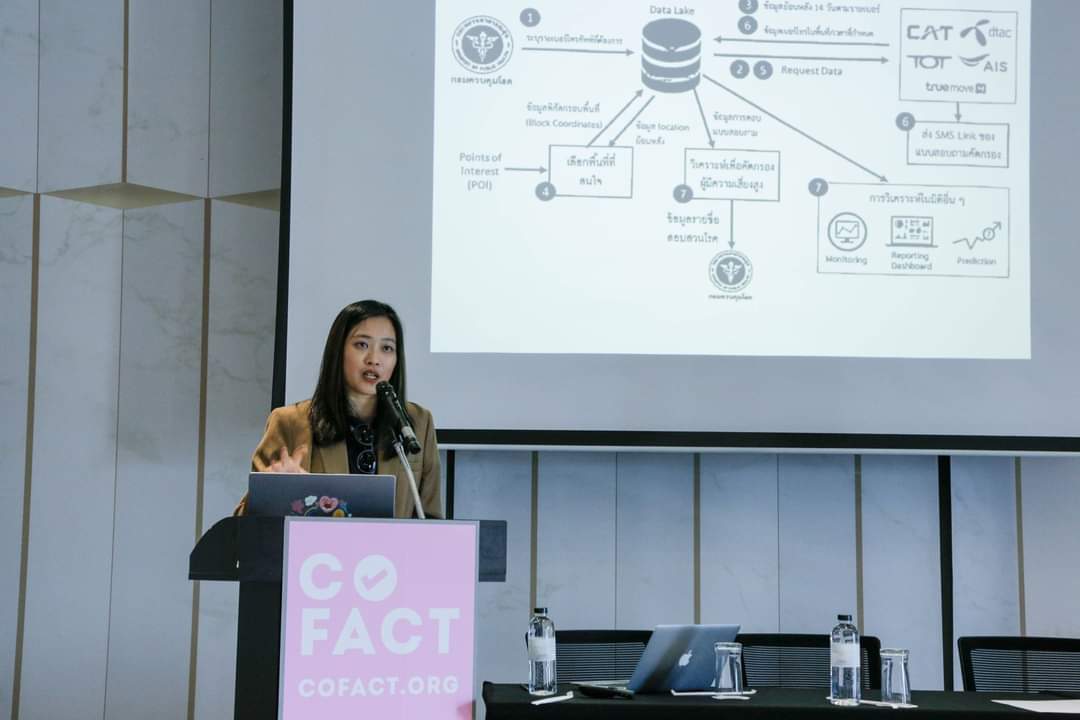

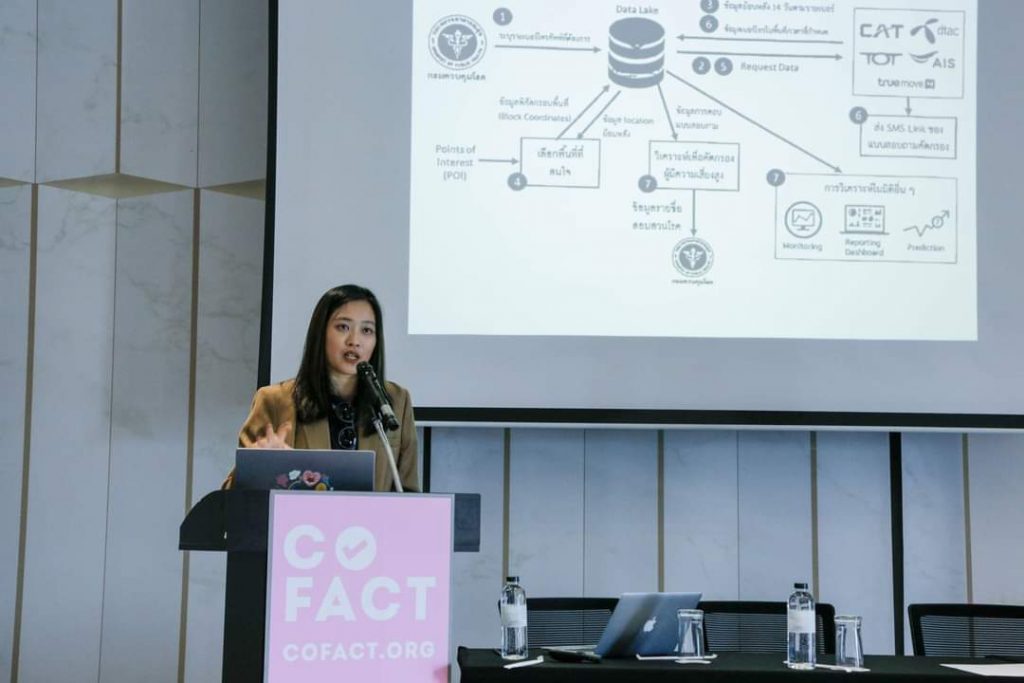

The fourth case refers to a request of Telecom Operators and the Department of Disease Control to seek phone numbers of citizens and link the numbers with risk areas. If the government is aware of Covid-affected zones, questions remain about the necessity of use of contact-tracing application.

Privacy rights in the Thai context

Views on privacy differ wildly between Asian and Western cultures. In Thailand, extended family networks dominate rural areas, answers for personal questions such as what grade are you in?, where do you work? and who will you marry? can be “revealed”.. The westerners, in contrast, aren’t used to “poking their noses into other people's business”. Thus, people in the West place “considerable emphasis” on privacy while Thai people in rural areas see this curiosity “common”.

According to Prof. Pirongrong Ramasoota, Faculty of Communication Art, Chulalongkorn University, said even Thai people living in urban areas view privacy differently from rural populations. For example, having the health volunteers on the coronavirus frontline may be seen as invaders of privacy for urban residents but people who are living in rural areas feel safer when there are health volunteers monitoring those who undergo mandatory 14-day isolation and confirming that they are free from the virus and can return to normal lives after isolation.

In addition, Prof. Pirongrong said, there are two contact-tracing apps available today which are “Thai Chana”, or Thailand Wins and “Mor Chana”, or Doctors Win.

“The Mor Chana app has been rolled out because of economic concerns from the private sector. This application requires personal and sensitive data such as a permission to track GPS location. Since the pandemic situation at that time wasn’t bad, the app had not yet been so popular. Whereas, Thai Chana was launched with a Personal Data Protection Committee being in charge on May 15 when a nationwide lockdown was lifted. Later on, the Department of Disease Control held a series of meetings with Krungthai Bank (KTB) after May 22 when the Department realized they are actually data controller,” she said.

“Thai people aren’t casual about privacy and believe information they see in a television or computer is reliable enough. But we must not forget that cybercrime exists. Our personal data is very significant. If the users give away their personal data easily, cybercrime rates are expected to continue rising. Policy makers, including the Department of Disease Control, have responsibility for several key decisions in caring for personal data in order to make sure data is perfectly safe from online thefts,” said Prof. Kanchana.

Today, several mobile applications require ID number for registration. In Prof. Kanchana’s opinion, the users must think whether giving out personal information is worthwhile. Personal data protection involves three parties – users, policy makers and software developers, who play a key role in addressing the cybercrime.

During a Q&A session, Prof. Kanchana also highlighted the fact that the context plays an important role in shaping different views of privacy among Thai people.

“Rural residents could not care less about privacy, compared to urban population. We will gradually get used to the data being stolen if we don’t realize negative consequences. In case of village health volunteers, they’re able to know every single details of community members because it’s the way of life in Asia, including Japan. Unlike Europe, different culture and population density make their people aware of privacy,” she explained.

Nevertheless, questions remain about Thailand’s standards on disclosure of personal data in rural and urban contexts while making the general public feel safe from coronavirus outbreak and cybersecurity threats. The degree and strictness of law enforcement must be increased to address the commingling of personal data by those who did it without taking any proper precautions. In digital era, information is spreading rapidly. Thai way of life may pose a risk for data security and eventually lead to rising cybercrime.