50 years after ‘October 14, 1973’: Media Freedom Still Underway. High Expectations in the ‘Digital Age’ Urging Resolution”

October 19, 2023, the National Press Council of Thailand, the Thai Journalists Association, Thailand Consumers Council, Thammasat University, COFACT (Thailand), and ThaiPBS jointly organized Media Forum #20, “50 Years after October 14, 1973, and the Communication Rights in Thai Society.” The event took place on the 5th floor of Thammasat University’s College of Innovation (Tha Phra Chan) and was live-streamed on the Facebook pages of ThaiPBS, COFACT, the National Press Council of Thailand, and the Thailand Consumers Council.

Asst.Prof. Chayakrit Asvathitanont, Ph.D., Dean of College of Innovation, Thammasat University, welcomed the attendees, emphasizing that despite 50 years having passed, there are still lessons to be learned from the October 14, 1973 uprising. This event provides an opportunity to gain diverse perspectives from 5 generations of speakers on what is widely believed to be a major victory for the people, especially in terms of freedom of communication in Thai society.

“Organizing this forum, I can feel the intention of the organizers to present important knowledge to all participants, hoping that each one of you will gain knowledge and different perspectives from today’s forum. On behalf of the College of Innovation, we hope that there will be opportunities to open up the college as a public space for discussion and exchange on various issues that will benefit the public and society in the future,” said Asst.Prof. Chayakrit, Ph.D.

Ms. Nattaya Chetchotiros, Vice President of the National Press Council of Thailand, opened the event, noting that 50 years have passed since the events of October 14, 1973. Comparatively, this timespan marks middle age in a human’s life, much like how she views society, both from a media perspective and as a Thai citizen. She has witnessed both progress in the right direction and ongoing challenges, especially on the issue of freedom of communication in Thai society, the primary focus of this forum.

The events of October 14, 1973, have become emblematic of Thai society. During that time, students and the public mobilized to demand freedom, including freedom of the press, particularly for printed media, which played a pivotal role as a counterbalance to state authority. While broadcast and television media remained under strong state control, October 14, 1973, held a significant place in the annals of rights and freedoms.

Nonetheless, the subsequent incident on October 6, 1976, saw state-controlled media being used as propaganda. Following that, the order of RF.42 imposed a decade of media restrictions before the era of media liberalization began. And it has now transitioned from the 4th industrial revolution era into the digital era, with smartphones, online social media, and most recently, artificial intelligence (AI) taking on some roles traditionally held by mass media. This poses exciting, challenging, and thought-provoking changes in an era of intense competition.

“Although the media landscape may have gained more freedom, the expectations of Thai society have not diminished. They have, in fact, increased, especially amid information overload where consumers seek the truth. But who will be the gatekeeper of that truth? It is undoubtedly the role of mass media. Therefore, it begs a question: After 50 years, is the mass media still acting as the fourth estate in presenting the truth as resolutely as before?” stated the Vice President of the National Press Council of Thailand.

Ms. Saree Aongsomwang, Secretary General of the Thailand Consumers Council, stated that from her experience of working to protect consumers for many decades, she has observed an increase in media freedom. However, amidst the current societal changes, which encompass various types of media, influencers, content creators, and everyone involved in communication, there are varying degrees of freedom. But the one thing that consumers want to see and expect is truth and fairness for all.

Freedom must be accompanied by responsibility and ethics, especially when considering the challenges of the digital age. For instance, even the Thailand Consumers Council fell victim to fraudulent Line accounts in a recent incident. This raises the pertinent question of how we can discern whether Facebook pages belong to genuine media or individuals. It’s a complex task, given our immersion in the intricacies of the digital realm. If we aspire to effect change, we need substantial effort to be on the Twitter trend. This is no small endeavor, as modern society is now divided into numerous specialized groups.

“Even the changes that should be progressing forward are difficult, take, for example, global warming and environmental issues that everyone should collectively agree on. We are in the midst of a progressively challenging working environment. Therefore, we hope that media freedom will continue to be a driving force for ongoing change in these areas and remain strong,” stated the Secretary General of the Thailand Consumers Council.

Mr. Sommai Paritchat, Managing Director of Matichon Public Company Limited and former President of the Thai Journalists Association, delivered a keynote speech titled “Viewing Thai Media: From the Fourth Estate to AI Journalism – How Far Have We Come?” He depicted the landscape of freedom of communication in Thailand, which has fluctuated over the years, influenced by the political context at the time. During the years 1937 to 1947, Some periods witnessed an increase in printing rights, the establishment of political parties, and public demonstrations, while in other periods, certain aspects of freedom were curtailed. In some extreme cases, there were even assassinations of political opponents and mass media journalists.

As the year 1957 approached, Thailand entered a long era of military rule following the coup d’état led by Field Marshal Sarit Thanarat, and then his successor, Field Marshal Thanom Kittikachorn. This dark era saw extensive control and suppression of media professionals. Article 17 of the constitution granted those in power sweeping authority, while the process of drafting a new constitution lagged behind. In this climate, the public, especially students, demanded democratic reforms, leading to the significant event of October 14, 1973.

However, freedom was short-lived. Just three years later, on October 6, 1976, it all came to an end with a military coup. Media outlets were ordered to be shut down and controlled under the order of RF.42. Those who couldn’t endure this had to escape into the forests. Subsequently, General Prem Tinsulanonda issued Policy 66/23, allowing those who had escaped into the forests to return to society. This was followed by the government led by General Chatichai Choonhavan, which revoked the order RF.42, restoring media freedom once again. However, in 1991, the government was overthrown, leading to the events of Black May in 1992, which ultimately led to the creation of the 1997 Constitution.

The 1997 Constitution was referred to as the People’s Constitution, amid a society that was awakening to greater freedom, including in the realm of communication. This led to the establishment of laws governing news information and the allocation of broadcast frequencies. Then after another Coup in 2006, there were new laws introduced, such as the Computer Crime Act, the Broadcasting and Telecommunications Organizations Act, and the Printing Recordation Act, which, while appearing to promote freedom, also introduced laws like the Security Act.

2007 to 2017 was an era of transformation. Digital TV channel licenses were auctioned, and online media began to play a more significant role, “from print to digital media”. However, what followed was a fierce business competition for survival, with more focus on staying afloat rather than producing content as it should have been. Nevertheless, some online news agencies gained recognition, such as Isranews Agency. Yet, due to the reliance on foreign platforms, concerns about cyber sovereignty emerged. Furthermore, after the 2014 coup d’état, new laws were introduced, such as the Public Assembly Act and the Personal Data Protection Act (PDPA).

In summary, government-issued laws often lean towards constraining the people’s freedoms rather than enhancing them. Moreover, the government’s closed systems and the significant impact of state secrets make it challenging for both the media and the public to obtain news information. While professional media organizations have grown in prominence, they still have limited roles in upholding ethical standards and safeguarding the public’s freedoms, as they must struggle for survival. Society’s power is not yet strong enough, even though technology has made it easier to access news information.

In conclusion, what lessons can we draw from the 50 years after October 14th, and lessons for whom? For 1. Those in positions of state power: If you misuse your authority, wield it without restraint, stifle freedom, and suppress the media, you will ultimately face dire consequences. Democracy and freedom under responsibility remain the most prudent course of action. 2. Mass media: You must establish strong independent news agencies, performing your role alongside mainstream media. Elevate the concerns of the common people, not just those of the elites. News with substance should take precedence over sensational news or bizarre stories.

“Communication rights in our society and the era of digital journalism should evolve further. The hope lies in the power generated by the collaboration of media organizations and the consumers council, fostering truth, news, and mass media empowerment in all aspects, ultimately strengthening the people’s power,” said Mr. Sommai.

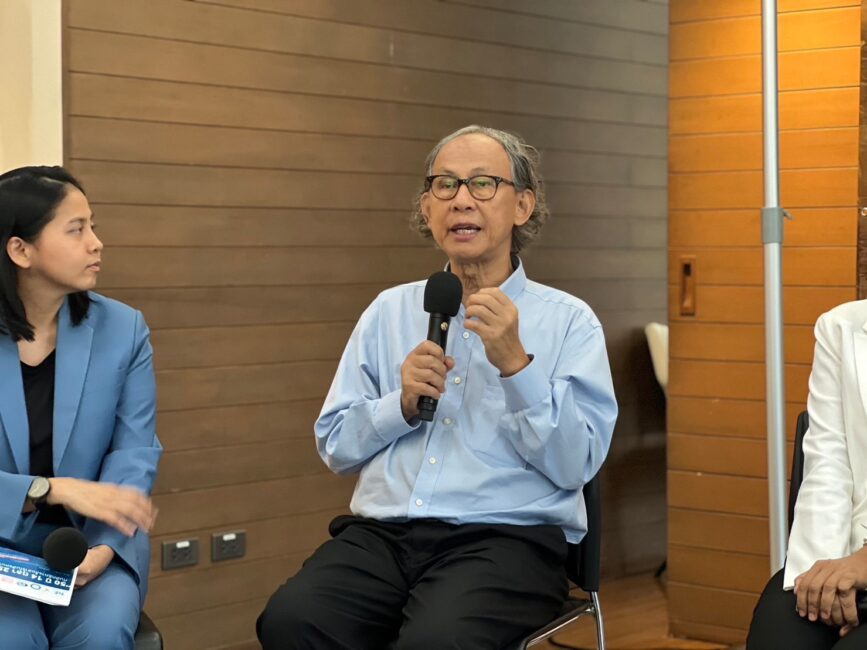

Following that, the forum began with the topic of “Reflecting on Lessons Learned and Moving Towards Truth and Justice: A Perspective from 5 Generations,” Mr. Kavi Chongkittavorn, a distinguished panel member of the National Press Council of Thailand, started the discussion, focusing on three current situations in Thai society:

1. Information Overflow: The rise of social media has led to an abundance of information. However, this abundance lacks filtration, making it difficult to distinguish real from fake news. The quality of news is not adequately assessed. In the past, news reporters had to be physically present at events to cover them, whereas today, information can be gathered from social media.

2. Journalists in Thailand need to enhance their skills. They tend to report events as they unfold but may not revisit the story if there are no new developments, even when persistent societal issues are at play. Journalists should grasp the context and ongoing events. Some international viewpoints recommend that online news agencies employ experienced editors to ensure news reporting isn’t solely focused on speed.

3. Artificial Intelligence is the media’s foe.

“The current circumstances, both domestically and internationally, along with the challenges within editorial teams and with economic conditions, are driving our journalists to enhance their skills to match the freedom we have, rather than placing blame on Thai society when we lack the proficiency. Thai society enjoys freedom, but the media’s capabilities need to catch up with the available freedom. There’s a gap. Some countries have little or no freedom, yet their media excels due to their proficiency, like Singapore. They have only this much freedom, but their media’s capabilities make up for any gap,” said Mr. Kavi

Ms. Supinya Klangnarong, the co-founder of COFACT (Thailand) and the Chairperson of the Media Consumer Protection Working Group at the National Press Council of Thailand, compared the issue of media freedom in two eras: the 1970s, during the global Cold War when countries were divided into liberal and socialist factions, with both sides waging information warfare while developing countries trying to assert control over their own communications.

In the present era, although similar circumstances exist, online platforms have introduced significant changes. The forms of problems have also evolved, such as misinformation, disinformation, fake news, and the post-truth era, where the line between reality and falsehood blurs. While the media is expected to deliver the truth, sometimes they become purveyors of fake news due to the influence of online echo chambers.

“Lastly, in terms of structure, have we made any progress? I’ve been following this for 20-30 years, from the late 1990s to the present. Thailand has laws that should cover almost everything, mechanisms that should be in place, funds, oversight organizations, and legal frameworks – everything that should be there, and in many aspects, we’re doing better than many other countries. People applaud our work, but some still wonder why it’s not good enough. So, I’m not sure if the expectations of Thai society are exceptionally high, or if we haven’t found the right path yet, or perhaps we’ve found it, but we need to keep moving forward. We’ve reformed structurally, but the 100% change that hasn’t occurred is in the cultural aspect, hasn’t it?” said Ms. Supinya.

Mr. Pongpiphat Banchanont, the Editor-in-Chief at Nation Online, discussed challenges within “Media and the Masses” in three aspects: 1. Building Trust: In recent times, the media has faced increasing scrutiny. 2. The Role of Professional Media in a rapidly changing society: There are discussions on whether Journalists and Content Creators can coexist. And 3. Media as a Business Entity: In the past, suppressing media freedom involved using direct power, even resorting to killing. However, the present landscape has become more complex, involving sponsorships and various forms of influence, making it difficult for the media to function smoothly.

Within the “Media” itself, there are also three aspects: 1. Generations in Media: Varying perspectives on certain issues. 2. The Challenges in Defining Media: This becomes apparent in discussions surrounding the Media Act draft, or the interpretation of media that is exempt from personal data protection laws. Some limit it to traditional media, while others regard both traditional and online as media. And 3. Media Collaboration for Negotiation: The collaboration among media organizations can be effective in negotiating for freedom and business matters. However, some observations question whether some groups authentically represent the media industry.

“Especially in the past five years, there have been numerous cases of people criticizing the media associations. I’ve consistently mentioned that people criticize because they have expectations. But where do we stand when people need us? We have no clear answer. To the extent that there have been meetings to establish new media associations that can address this, I don’t know if it’s a stroke of good luck or bad luck. I’ve been involved with at least three groups in the effort to form media coalitions for negotiations, particularly concerning the freedom and well-being of journalism in the field, going deeper into the quest for truths,” said Mr. Pongpiphat.

Ms. Anchan Anchaisri, a Digital Journalist from Workpoint Today, stated that she was born in the analog era but works in the digital age. She has noticed differences in “pushing the news boundaries” on certain issues. However, the outcome has led to numerous legal actions against media agencies and cases of harassment against journalists and news agencies. Anchan couldn’t define this as a restriction on freedom or as freedom with repercussions. Regarding the future of the media, she expressed its unpredictability, especially for consumers, which poses a significant challenge to the media.

“I would like to emphasize that we still have hope for quality media, media that is free. I feel that there is still hope. In my three years of work, I still have hope, but I am one of those who are searching for how this hope will materialize. What will be the method? Is there a model, or what needs to be done? There is hope, but I don’t know the way to achieve it because there’s no fixed, one-size-fits-all solution. But what can be a driving force to propel the media forward is having a dedicated team and editors who consider all aspects of the issue,” said Ms. Anchan.

Mr. Kunakorn Tantichinda, President of Thammasat University Student Union (T.U.S.U.) mentioned that various social media platforms have made everyone their own media, and although the development of media freedom has had its ups and downs over the years, what remains constant in every era is the conflict between the stability of the state and issues of rights and freedom. Despite the appearance of greater media freedom in recent times, the government still seeks ways to control the media, albeit at a slower pace. Whereas in the past, when there were only a few media outlets, it was easily controlled by the government.

On the other hand, due to the abundance and dispersion of media, making it uncontrollable, there is an issue of information accuracy and media ethics. While everyone can disseminate information through social media, not everyone has undergone the study of communication and media. However, without media freedom, accurate information cannot be ensured because there will be only one-sided information. In summary, we have come halfway with media freedom, but what lies ahead is the accuracy of information and media ethics.

“The extensive and uncontrolled spread of media has led to a peculiar phenomenon known as the ‘Echo Chamber.’ It means that while everyone can express their views, it unintentionally gathers people with similar views into the same space. This is a concerning trend in our current age. If we look back to the October 14th and the subsequent October 6th event, we can see that the media played a significant role in shaping these occurrences. We certainly wouldn’t want another Echo Chamber to lead us down a similar path, not just in Thailand but in other seemingly developed countries as well. Many countries are grappling with issues related to the Echo Chamber,” said Mr. Kunakorn.

In the closing remarks, Asst.Prof. Uajit Virojtrairatt, Ph.D., Vice Chairperson of the Media Consumer Protection Working Group at the National Press Council of Thailand, stated that the events of October 14, 1973, were pivotal in making society recognize the importance of media freedom. While media quality is something to aspire to, expecting media freedom without collectively nurturing it is unrealistic. Media freedom and media quality are intertwined. It’s worth noting that during the era of October 14, Thailand was under a military junta, having Semi Democracy. However, even today, we continue to seek true democracy, one that arises from the people and listens to the voices of the people.

“Beyond discussing the need to collectively raise media freedom to its highest level and improving the quality of the media, what’s commendable is the dialogue among different generations, from Baby Boomers, Gen X, all the way to the youngest generation. In the end, it’s a challenge, it’s exciting, and it brings hope. And under that hope, the value of working together among different generations is recognized,” said Asst.Prof. Uajit.

In addition, there was also a joint declaration on the “Rights of Communication in Thai Society, 50 Years After October 14, 1973,” stating that media freedom and the right to communicate are fundamental human rights demanded by both the media and society. Professionals in the media and the people of Thailand united to demand these rights from the authoritarian government, particularly in the events of October 14, 1973, which is considered a significant milestone in the collective effort of students, scholars, and the public to advocate for the principles of liberty, equality, and fraternity.

After five decades have passed, freedom of media and the people have been enshrined in several versions of the Thai Constitution. On the whole, mass media has seen an increase in freedom. Nevertheless, there are still limitations in both legislation and enforcement, particularly regarding fundamental legal and ethical aspects of mass media. These issues continue to be a concern within society, running parallel with the use of mass media freedom. In the digital age, social media has become a platform where the public disseminates content akin to mass media. Frequently, online communication leads to confusion, misinterpretation, and animosity, making it a challenge to verify the accuracy of news circulating today.

However, whether in the era of October 14, 1973, or in the era of October, 2023, society still aspires to have mass media serve as a platform for presenting accurate information based on fairness for everyone, thereby helping to bridge societal gaps, reduce disparities, and mitigate conflicts and animosity. Moreover, there is an expectation of credibility in mass media, being the voice of the public, and providing a system of checks and balances against state authority.

In the meantime, although media consumers in this era have various options for receiving and communicating information, they must also develop their knowledge and understanding, or media literacy as well. This includes not forwarding information that may have an impact on themselves and society. As we commemorate the 50 years after October 14 this year, we express our commitment to the following principles:

1. Media freedom is the cornerstone of a democratic system. We urge the government, regulatory bodies, and state agencies to consider it their responsibility to safeguard and support the work of mass media and civil society while ensuring a direct and transparent system of checks and balances. The state should grant autonomy to organizations related to media and communication, such as NBTC and professional mass media organizations.

2. We call upon all types of mass media, including individuals with roles in online communication (Key Opinion Leaders/Influencers/Content Creators), to uphold ethical practices in presenting facts, refraining from distorting information that may harm the public interest. It is crucial to establish self-moderation guidelines and to mutually oversee one another to uphold the value of freedom alongside responsibility.

3. We urge media platform providers to collaborate with civil society in establishing content moderation guidelines aligned with community standards. This should be based on principles of upholding freedom and shared responsibility to reduce violence and hatred in society.

4. We request the government promote public policies that protect consumer rights, civic rights, and communication rights in the digital age fairly and equitably. This includes supporting consumer empowerment by facilitating easier and increased access to communication and information.

5. We urge a comprehensive review of laws, regulations, and rules that may hinder the promotion of communication rights, including governance mechanisms related to mass media and communication. This review should involve the Parliament, with active citizen participation, and the drafting of a new constitution under the Constituent Drafting Assembly of a truly representative of the citizens, to ensure a constitution that promotes freedom, equality, and the decentralization of power, both in local governance and in the right to use radio frequencies for people’s media and community media nationwide.

-/-/-/-/-/-/-/-/-/-/-